Vanishing Habitats in a Growing City

Ask anyone who has lived in the city long enough, and they’ll tell you it once felt very different. It was cooler, greener, and far less dense. Tree cover was more continuous, lakes functioned as wetlands, and scrublands were part of the landscape rather than something to be cleared.

That version of the city has changed rapidly. What we usually focus on are human inconveniences—traffic, heat, longer commutes. For wildlife, however, this transformation has meant something far more severe: the steady loss of habitat.

As cities continue to expand outward, habitat loss has become the single biggest driver of biodiversity decline in urban landscapes.

Where Did the Wild Go?

Habitat loss isn’t just about visible tree cutting for roads or infrastructure. It is tied to how urban development happens and which landscapes are considered expendable.

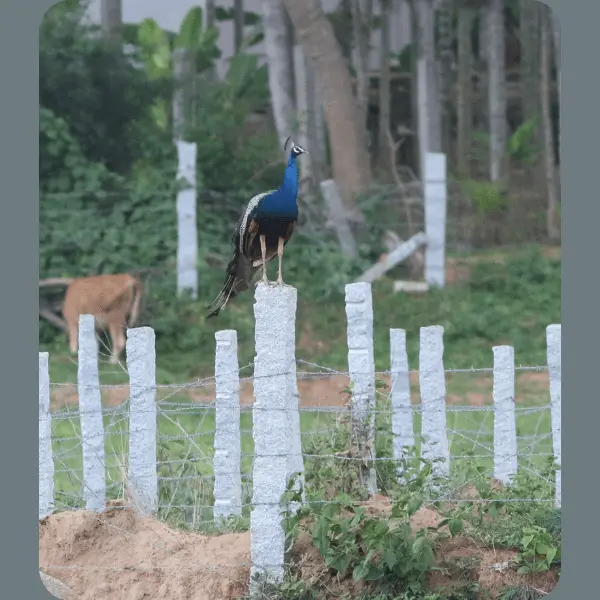

Scrublands dismissed as “wastelands” : Urban peripheries are often dominated by scrub forests and grasslands. These areas are frequently labelled as vacant or degraded, despite supporting a wide range of species. As development advances, these ecosystems are flattened, fenced, and built over, displacing mammals, reptiles, ground-nesting birds, and insects.

Fragmentation of remaining green spaces : Isolated parks and lakes cannot function as complete ecosystems. Wildlife depends on connectivity to move, forage, and breed. When roads, layouts, and compound walls cut across landscapes without corridors, populations become isolated. Over time, this leads to reduced breeding success and local extinctions.

Green spaces that don’t support life : Even where greenery exists, it is often simplified—lawns, ornamental trees, decorative palms. These spaces may look green, but they offer little food or shelter. Compared to native vegetation and undergrowth, they support only a fraction of the biodiversity.

What Happens to Wildlife

When land is cleared or wetlands are filled, animals do not simply relocate.

- Arboreal mammals depend on continuous canopy to move and breed. Removing mature trees fragments their range and isolates individuals.

- Waterbirds rely on reed beds and shallow wetlands. Replacing these with stone embankments and paved paths removes nesting and feeding areas.

- Pollinators decline when native host plants are replaced with ornamental species.

- Reptiles lose basking sites, shelter, and prey. This is why sightings inside buildings increase—not because animals are encroaching, but because their habitats have been removed.

Why This Matters to People

Habitat loss has direct consequences for urban life.

Scrublands and wetlands absorb rainwater. When they are removed, flooding becomes more frequent. Insectivorous birds and bats help regulate insect populations; when they decline, mosquito numbers increase. Biodiversity loss directly affects how cities cope with environmental stress.

What Can Be Done at a Community Level

Urbanisation cannot be reversed, but it can be managed more thoughtfully.

Rethink gardens and green spaces : Even small areas can support life. Native plants provide far more value than exotic ornamentals. Leaving patches of soil or leaf litter undisturbed supports insects, reptiles, and ground-nesting species.

Question tree felling : Tree cutting without permission is illegal under state law. Even when approvals exist, nesting checks are mandatory. Delaying felling until chicks have fledged can prevent entire breeding failures.

Protect canopy connections: Trees that touch or overlap form movement pathways for wildlife. Removing a single mature tree can break an important corridor. These link trees often matter more than they appear to.

Support restoration, not cosmetic upgrades : Planting saplings has value, but protecting existing habitats is far more effective. Ecological restoration should prioritise function—wetlands, undergrowth, and native vegetation—over paving, lighting, and visual appeal.

Coexistence needs planning and policy support

Cities do not have to choose between development and ecology. Coexistence depends on planning, restraint, and recognising that not all open land is expendable. Protecting remaining scrub, wetlands, and tree cover is not about preserving the past—it is about ensuring that urban environments remain livable, functional, and resilient in the future.

Leave a Reply